“unWILLingly … If me so bad, medivac’acked immediately” and “If cool-aid, celestially unredeemable”.

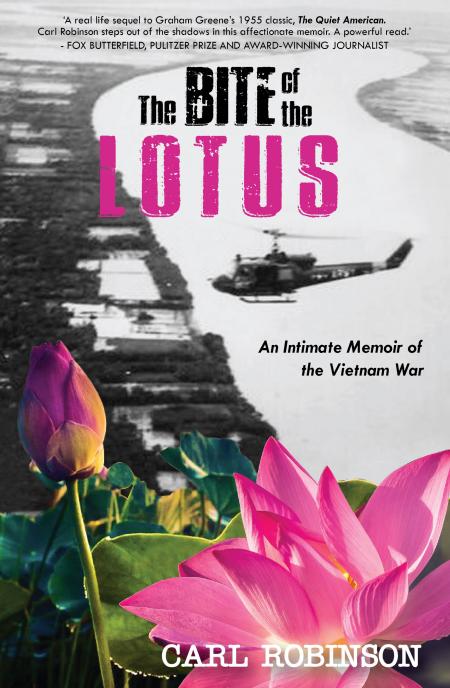

Edited extracts from the new book,The Bite of the Lotus: An Intimate Memoir of the Vietnam War, by Sean’s friend and photojournalist colleague, Carl Robinson

…

I’d arrived in South Vietnam in early 1964 as an idealistic 20-year-old who grew up in the Belgian Congo and had spent most of my life as an expat. I’d become enchanted with South Vietnam as a visiting university student from Hong Kong and returned to a job in the US-run pacification program, or winning hearts and minds. Quitting in protest after the Tet ’68 Offensive, I drifted into journalism to stay on with the Mekong Delta maiden who’d captured my heart. I’d seen a lot and my initial idealism was a fast-receding memory.

I’d also met a lot of people. Foreigners and Vietnamese. Military, spooks and aid workers. And now a band of reporters and photographers looking for fame, if not fortune, covering a war that had already turned into a seemingly endless quagmire.

Over at the quieter end of the room, by a large open window, I saw someone about my age sitting quietly and alone in a high-backed rattan chair, observing the scene. Tall and handsome with a thin moustache, he was Sean Flynn, son of the actor Errol Flynn. I wandered over to introduce myself.

We found that we had a lot in common. We were both fluent French-speakers, life-long expatriates and comfortable drifting between different cultures, as well as being constantly curious and well read. Sean had spent time in Africa and wore an elephant hair bracelet.

By April 1969 it seemed like things were starting to unravel. I’d just returned from a memorable motorbike trip with Sean through Laos – in which we’d narrowly avoided the Communists and deepened our friendship in the process – when I rode my bike into a barbed wire barrier strung across a Saigon street.

The incident would mark the start of a string of departures and other mishaps in my circle of friends. Most shockingly, (photojournalist/friend) Tim Page was badly wounded by a booby-trapped US-made 105-mm artillery shell west of Saigon. The right side of his brain was blown away, and he was now at the 24th Evacuation Hospital at the huge US base of Long Binh, north-east of Saigon.

Sean heard the news in Vientiane and rushed back to Saigon. Sitting together in the rumble seat of the yellow Citroen convertible of David Sulzberger, son of New York Times columnist Clive, on our way out to Long Binh, Sean was quieter than usual. But when we got there, he purposefully made light of what happened, saying: “You’re crazy, Page, what’d you do that for?” Touchingly, Sean gave Tim a wooden statue from the Cave of One Thousand Buddhas, just upriver from Luang Prabang in Laos, which he’d visited after I left to come back to Saigon.

Clearly, something had happened to our old gang. Just Sean and I were left. He was clearly shaken, and several days later presented me with a handwritten note beginning with the word “unWILLingly”, and including instructions for if he was wounded or killed: “If me so bad, medivac’acked immediately” and “If cool-aid, celestially unredeemable”.

He also noted addresses and to whom I should send his belongings. Sadly, Sean said nothing about what to do if he just disappeared.

Perhaps thinking of our experience in Vietnam and Laos, Sean rented motorbikes for himself and Dana and, along with other journalists in four-wheeled vehicles, headed south-east of Phnom Penh down Route 1, across the Neak Luong ferry over the Mekong River, and then east into the Parrot’s Beak, where the Cambodian border pokes like an arrow into southern Vietnam.

But the Communists, unsure of what would happen next, quickly sealed off the border region and erected roadblocks to halt normal traffic. Just west of a roadblock only a dozen kilometres into Cambodia, correspondents saw a stopped sedan with its doors open. Only the previous day, two French photographers, including my friend Claude Arpin, had disappeared near here, probably a bit further down the road.

What happened next, on that early April day of 1970, is now the stuff of legend – and personal anguish. Eyewitnesses had seen my two friends arguing in a cafe, with Sean trying to talk a reluctant Dana into pushing further down the road. Finally, they hopped on their bikes and, with only a few words, rode past the other waiting journalists straight towards that roadblock.

They were never seen again. Missing, presumably captured.

As reports of their disappearance came into the AP office the next morning, I couldn’t help smiling as I recalled how often Sean and I had fantasized about slipping over to cover the elusive “other side”. It was the holy grail. We’d be welcomed with open arms, take pictures, do interviews and come out with the scoop of the Vietnam War. Sure, I thought, they’ll make it. Just give ’em a few days.

But as days turned to weeks with no news, I was filled with foreboding and despair. And guilt, too. What if I hadn’t been caught and expelled trying to sneak into Cambodia only three weeks before?

It’s certain I would’ve been there too on that fateful day on my own rented motorbike. Would I have backed Dana and refused to go any further? Or would I have followed Sean? I have lived with that torment ever since.

Sean had given me that handwritten will in case he was killed or wounded, but he’d said nothing about what to do if he just disappeared. I was stunned and felt helpless.

— Tim