O to be in England, now that April’s there. I doubt Errol yearned his living like Browning, but for once Browning would be right as it is presently 7pm, 25 degrees (about 76 F) and ne’ry a cloud in the sky. This turns a girl’s thoughts to cocktails.

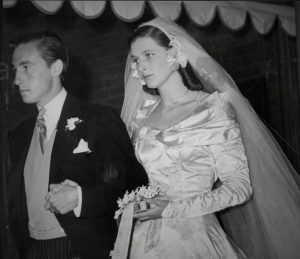

When Errol and Pat were in Rome in the 50s they met a charming young English girl called Diana Naylor-Leyland. She was not only charming but had a laser like intelligence and great poise and beauty. I can vouch for this because she was to become a beloved friend of my family.

Diana used to spend summers with us in Italy, and when I was old enough to drink – I think I was about 12 (only half joking) – she taught me how to make a fabulous and lethally ‘refreshing’ cocktail.

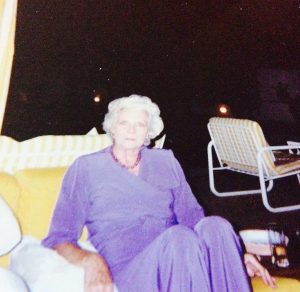

Diana, below, snapped by me in Italy

After I had expressed my appreciation, at both the taste and the effect, Diana informed me she had been taught to make it by Errol – and that it was his own invention. Naturally, yours truly fell at her delicately sandaled feet.

All those years ago, Errol had taken quite a shine to Diana. She lunched with him at various restaurants in Rome for about four months. However, Errol never once made a pass at her (she was a very well brought up, elegant and educated girl).

I asked Diana what she had though of Errol and she said, ‘He was not at all what I expected. Nothing like the ‘image.’ ‘

She remembered him as being rather shy, very polite, sweet and keen to Errol on about books and the Classics.

Pat liked Diana, too, and she was asked to become their social secretary. When Diana told her father, however, he reacted as most fathers would have done – boringly – and forbad it. But she continued to see Errol, before returning to England to get married. She was later to become the Countess of Wilton.

On to the drink. Errol’s aforementioned cocktail – which he had created himself – was a variation on the classic White Lady (he favoured variations on white ladies, as we know). Errol dispensed with the egg white nonsense and invented a cleaner, tarter and more masculine drink which was served in a martini glass.

Diana, who, like me, had been introduced to liquor at an early age – used to imbibe it with him, and asked him for the recipe. After some coercion, she not only passed it down to me, but wrote it down. I blessed the piece of paper, and immediately christened the drink ‘The Errol Flynn.’

Below: Errol at a drinks party in Rome (with La Lollo), but with the wrong drink!

This is a cocktail to be taken very seriously. It is like being handed the original recipe for Nectar by a friend of Ares or Apollo. Making an Errol Flynn is an historic ritual and takes time, love and effort. But I promise that the results are more than worth it.

So here is Errol’s very own invention.

Ingredients (makes enough for two people)

3 large and juicy lemons and 1 small lime

Gin (Beefeater’s or Tanqueray)

Cointreau

You will also need Martini glasses that have been in chilled in the freezer, a measuring jug and a proper cocktail shaker.

Method

Squeeze lemons and lime and strain the juice. Pour the juice into the measuring jug.

Add an equal amount of Gin to the jug and stir.

Add an equal amount of Cointreau and stir.

Fill the cocktail shaker with ice and pour in the mixture. Shake until the shaker is so iced over that you are screaming in pain.

Pour the contents of the shaker (without adding any ice) into the chilled glasses and drink immediately. Then have another (preferably with a cigarette).

Do not ever add an olive or a twist. This cocktail, like Errol, is a Rolls Royce and needs no embellishment.

However, pistachio nuts, Sicilian olives or wild boar salami go very well with this drink as nibbles.

— PW

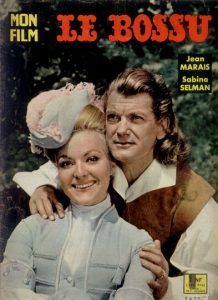

Doug Fairbanks Jr and Ronald Colman in ‘The Prisoner of Zenda.’

Doug Fairbanks Jr and Ronald Colman in ‘The Prisoner of Zenda.’